Ntiamba Obi Ntui (Cyprian)

About the Book

Virtually every individual, group or nation is concerned about issues of development. Too, everyone can contribute to meaningful development in one way or the other. But because many human beings live their entire life time without discovering their innate potential, they end up not making commensurate contribution to the progress of even their immediate community or village. Development is ultimately retarded when so much human potential is locked up and gets wasted at the end of every life. The role that the politics of a nation plays in mobilizing citizens and awakening their consciousness to participate fully in the development of their country cannot be under estimated. This is the main focus of this book. The essays are designed to free the reader’s imagination, sharpen his or her critical thinking and open the reader’s eyes to better understand and analyse socio-political and other happenings around them. The essays run through a gamut of issues from analysis of personalities to communal, national and international affairs. Reading through them will surely unveil your own potential and motivate you to show more interest, be active to become a participant in shaping the future of your community and nation.

About the Author

A Chapter of a Life

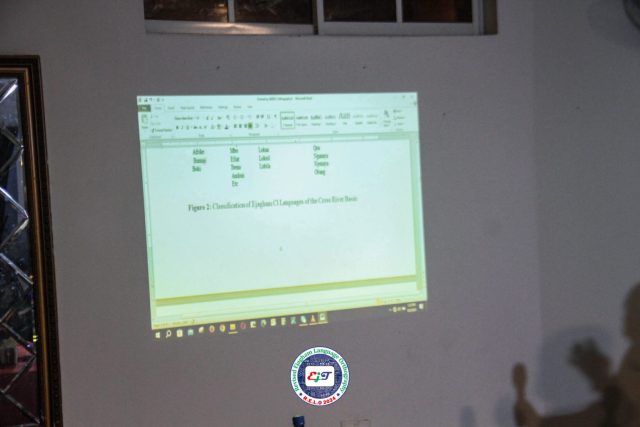

Ntiamba Obi Ntui was born in Ayaoke village, in present day Eyumojock Subdivision, of Manyu Division, South West Region of Cameroon. Ayaoke is one of the 66 or so villages that make up the three core Ejagham speaking clusters in Cameroon – Njemaya, Ngunaya, (or Ejagham Central) and Obang.

Ntiamba never knew his mother, whose name he learnt was Alice Aya Ndum. She was one of the female children born to Chief Ndum Nkom James, by Mma Agbor Asu, a woman from Mbeyan who got married to a man from Ayaoke. Both Mma Agbor and eteh Ndum outlived their daughter, Aya Ndum by more than two and half decades making it possible for Ntiamba to know his maternal grandparents very well. My mother’s elder sister, Akajoeh Ndum Regina, (Mma Regi) also outlived her junior sister by more than four decades also making it possible for Ntiamba to know her maternal aunt very well.

Apart from these relatives who were so close and impacted my life very much, my mother also had brothers from the same father but different mothers; as well as another sister and three brothers from the same mother but different fathers.

Ntiamba´s father also had brothers and sisters from the same father but different mothers but only one sister from the same womb, but a different father.

But it was my father´s sister, Mama Cicilia Eta Otang who actually assumed responsibility of taking care of Ntiamba in the absence of his biological parents. But since my aunt was married to Mr Ogen Ndifon Eta in Ekoneman, a neighbouring village to Ayaoke, the woman moved into her marital home in Ekoneman with little Ntiamba.

Unlike Ntiamab´s mother, Mr Obi Ntui James, the biological father, left behind a photo on his national identity card. The photo was enlarged after he died, which helped to preserve the memory of the father (Nseh Abon) to the children he left behind. By the time he passed away, he had nine children from three women.

This is a bird´s eye view of the complex family Ntiamba had to grow up with.

Ntiamba Goes to School

Though Mma Cicilia assumed responsibility over little Ntiamba, it required the help of virtually every member of this complex family, in order to see the boy through primary and secondary school.

As a child, Ntiamba used to see Mr Ntui Agbor Ojong, the Headmaster of Primary School Ottu, come to Ayaoke to scout for children who had reached school-going age. It was later on that Ntiamba learnt that Catholic Missionaries who came to the Eyumojock area in colonial times, created schools in villages with a sizable population, while smaller villages were designated as catchment villages for the four schools they created that were closest to Ayaoke. Primary Schools Ottu, Ekok, Eyumojock and Inokun. Ayaoke never had a primary school until the early 1980s.

Mma Cici took her little boy to Ottu and enrolled him in the primary school, when the Head master agreed that the boy was of school age, even though Mma Cici still considered me to be too small and fragile. Because of that she vehemently opposed my elder brother´s intention to take me to start school in Kembong, another village more distant from Ekoneman/Ayaoke where he was teaching at the time.

To Mma Cici, Kembong was too far away and she would not be able to check on how I was faring every now and then. Consequently, I spent the first five years of Primary School in Ottu, before my elder brother eventually moved me to Saint Martin’s Primary School, Kembong where I had my First School Leaving Certificate, FSLC.

At about the same time, I also wrote the Government Common Entrance Examination; passed and was admitted into the prestigious Saint Joseph’s College, Sasse, near Buea, the capital of today ́s South West Region of Cameroon. The school year was 1972/73. It is through this school year that I had continued to estimate my age, since nobody kept a record of my birth. Brilliant children in Cameroon enter secondary school within the ages of 10 to 12 years.

Since my elder brother who was my sponsor also had ambition to further his education, he got admitted into the then lone University in Cameroon, the University of Yaounde, to do a three-year programme leading to the award of a Bachelor’s degree in Geography. Consequently, he only succeeded in keeping me in Sasse for two academic years.

During the 1973/74 academic year, my elder brother sought and was granted an audience to see the then Minister of Education to plead my case. Based on my performance in class one and the first two terms in form two, the Minister consented and sent a letter to the Principal of Government Grammar School Mamfe, to offer me provisional admission into form Three, pending my third term form two result from Sasse at the end of the school year. I came sixth out of 120 pupils in form two so I was promoted to form three in Sasse.

I was to leave Sasse during the 1974/75 academic year because my sponsors could not pay the fees. I started school in form three at Government Grammar School Mamfe, that was to become Government High School Mamfe, before I could seat for my General Certificate of Education, `0` Level during the 1977/78 academic year. Being a government secondary and high school, fees were much lower than those in private secondary and high schools, (Colleges).

Even at that, schooling for Ntiamba became a joint project where my aunt and elder brother had to put heads together to see me through form five. Only those who know the South West Region of Cameroon very well can decipher what it meant for a student to be transferred from Buea to Mamfe, in terms of climatic differences. Life as a day student coupled with learning science subjects only in theory in a school without laboratories for biology, physics and Chemistry became the undoing of young Ntiamba.

The brilliant science student in Sasse became an average student in Mamfe passing six papers at `0` Level at the GCE during the 1977/78 academic year, all of them in the arts except for biology. With the good “0” Level results, my sponsors heaved a sigh of relief concluding that I had finished school, (Ntiamba aman nwed); whereas, right inside me, I was still far from getting done with schooling, (Nkaman nwed).

A New Life in Another Country

When it became clear that there was nobody in Cameroon to sponsor me further in school as the 1978/79 School Year started, I Crossed over to Ikom and met my father´s paternal cousin, Mr Clement Odi Ayamba, a man we still fondly call uncle Odi.

Now retired and resident in Acharum, Etung Local Government Area, of Cross River State, Uncle Odi then was working as a typist with Ikom Local Government. He was one of the early employees of the Cross River State Local Government Service Commission, under the 1976 Reformed Local Government System in Nigeria. Through his guidance, I eventually benefited from those reforms initiated by the Murtala Mohamed/Olusegun Obasanjo regime.

After tinkering with my age and nationality to suit the requirement of the Nigerian Public Service, uncle Odi mounted pressure, through the Chairman of Ikom Local Government who was his immediate boss, for the Cross River State Local Government Service Commission to employ me as a Clerical Officer, Grade Level 04, based on my GCE “0” Level results.

I was eventually deployed by the Ikom Local Government to the Treasury Department to work as an Accounts Clerk. Since he was aware of my academic ambition, Mr Odi encouraged me to apply for in-service training as an Assistant Executive Officer, AEO Accounts, when the training was advertised by the Local Government Service Commission, in Calabar.

I was sent on a nine-month training course in Local Government Accounting at the now Management Development Institute, Calabar, then Cross River State Civil Service Training Centre, in January 1979. I qualified by September of that year as an Assistant Executive Officer, AEO and worked as an AEO/Accounts on Grade Level 06, with the Ikom Local Government until September 1980.

That was when I again applied to be sent on another in-service training at the University of Nigeria Nsukka. I was sent there to do a two-year Diploma Course in Local Government Finance and Administration, in the Department of Political Science. Successful completion will enable me to qualify as an Executive Officer, EO/Accounts.

Though I qualified at the end of the 1981/82 academic year, I worked for five years, that is until 1985 before the Cross River State Local Government Commission considered me for promotion to the rank of EO/Accounts on grade Level 07. To many observers, my progress in the state civil service was too fast, provoking jealousy from those who claimed to have served for much longer without being sent on training.

Late 1983, I was transferred from Ikom to Akabuyo LGA. On my first day at Ikot Nakanda, capital of Akapuyo LGA, I met with Cosmas Effiom Ekong, the Chief Revenue Enforcement Officer of the council. He told me that when he saw my name on the posting communique, he knew I was Ejagham speaking. He welcomed me heartily on my arrival and did not hesitate to take me as his adopted son. Consequently, I stayed with him in his Atem Assam village house from where we rode on his motor bike to and from work at Ikot Nakanda, every working day. But that arrangement did not last long, because not long after, some newly created councils were merged, and Akpabuyo was one of them. This prompted the council to move back to Odukpani, from where Akabuyo was carved out. I found a rentable apartment at Federal Low-Cost Housing Estate in Calabar, from where I shuttled to and from Odukpani every day to work. Early in 1986, I was transferred from Odukpani to Akamkpa Local Government. There, I was posted by the council to serve as revenue officer for Urban District, with residence in Oban town.

Calamity and Education in Tears

From December 1983 to about the end of 1985, my life hung on a balance because of inexplicable ill-health. People attributed my illness to demonic or witchcraft attacks. I still cannot fathom from where they originated even as I am writing. So, my illness actually aggravated when I was working in Akapuyo/Odukpani LGA.

I was still single, with no child and still burning with the determination to further my education. So, when I recovered by the end of 1985, and having served my bond period, I decided to go back to school.

Before proceeding to UNN for the two-year Diploma course, I signed a bond to serve the Cross River State Local Government Service for at least four years after qualification. Surely, because of my youthful age, my employer foresaw that I will eventually not find fulfilment in the Local Government Service.

I decided to sit for the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board JAMB Examination but my “0” Level papers had expired.

The only way out was for me to rewrite the “0” Levels. I eventually had to enroll at the then School of Basic Studies, Akamkpa to rewrite both the “0” Levels and the JAMB Examination. I combined studies and work during the 1985/86 academic year. Sat for the two exams and passed both. Six “0” Level Papers like I did the first time.

I had admission during the 1987/88 academic year to pursue a four-year programme leading to the award of a Bachelor’s Degree in Sociology and Anthropology of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. My application for in-service training was rejected, so I had to leave my job for school with no reliable sponsor in view.

Consequently, it was a near miracle that I managed to graduate with a Second-Class Upper Degree in September, 1991 and was posted to Sokoto state for Youth Service.

Dabbling into Journalism after Youth Service

My Youth Service year coincided with the year new states were created in Nigeria. Kebbi State was carved out of the old Sokoto State. Therefore, when young graduates arrived the Ousman Dan Fodio University Sokoto pre-deployment training camp, they were randomly separated into two groups – Those in the first group were deployed to serve in the new look Sokoto State while those in the second group were deployed to serve in the newly created Kebbi State. I was among those who were posted to serve in Kebbi State.

After some hitches bordering on my posting to remote Government Secondary School, Yeldu, and unable to find accommodation there, I eventually did my service at Army Day Secondary School, Duku Barracks, Birnin Kebbi, present day capital of Kebbi State.

After service, I went back to Ikom, spent some time with the family there and crossed over to Ayaoke, where I also spent a few days. I moved to Mamfe and spent some days with the family before moving to Yaounde to see my uncle and family there. I then travelled back to Ikom.

By this time, we were already entering November 1991, the second month after my discharge from Youth Service. I could not spend much time in Ikom. I decided to go down to Calabar for job hunting. The Local Government Service Commission did not just want to listen to my explanations, having abandoned work when they needed me most. Akwa Ibom State had been created out of the former Cross River State, so the few trained staff of the Local Government Service in the new look Cross River State were expected to take over the mantle to build the young service with the mass movement of people to Akwa Ibom State. But I was nowhere to be found.

Towards the end of November, the Cross River State Newspaper Corporation, Publishers of the Chronicle Group of newspapers announced a mass recruitment of editors and reporters.

Those who showed up were given a written test from which those who succeeded were shortlisted for an interview. I came second, after Emerald Ojong, who had worked there, went into politics and could not make it, and wanted to come back.

I was eventually recruited as Editor 1 on Grade Level 09, with effect from 1 December, 1992. Realising that some of us who were recruited had no formal training in Journalism, the Nigerian Union of Journalists, NUJ decided to regularize our situation by sending us on in-service training at the International Institute of Journalism, IIJ Abuja. The training course was open to graduates working in the radio and television stations in Calabar, so IIJ made Calabar a satellite campus, to facilitate things for the crowd of those who needed to be trained. The Course lasted for nine months.

At about the same time, I also enrolled to pursue a Master’s Programme in Development Sociology, at the University of Calabar.

Marriage and Family Life in Calabar

When I got a job at the Cross River State Newspaper Corporation, I went to Ayaoke, and took Emelda Ekun Odu as my wife. We had our first child on 2nd April, 1995. I named the boy Eyunjui Ntiamba Obi Ntui James. With a baby in the hands of inexperienced parents, my wife and I needed someone to help with domestic work. So, I went again to Ayaoke and took one of my nieces.

Even after rising to the rank of Senior Editor on Grade Level 10, we could not make ends meet with my salary. Even worse was when I changed the money into Franc CFA in order to travel to Cameroon.

So, when I took my annual leave in July/August 1998, for the umpteenth time, I took the hard decision to leave my job again and relocate to Yaounde. When we crossed over, I enrolled Ekun in Government High School, GHS Eyumojock to do her `A´ Levels. Our son who was three years old by then got enrolled in the nursery school at Eyumojock. My niece re-joined her parents in the village to continue schooling in the Primary school. I then moved to Yaounde, beginning of September, 1998, again for job hunting.

I spent the first four months in Yaounde learning the realities of the way things are done differently in Nigeria and Cameroon. In academic pursuit, the system in Cameroon required graduates to first have the `A` Levels before going for any degree programme. Which means, the absence of the `A` Level Certificate for any one applying for a job meant automatic disqualification.

By January 1999, I started looking for a job in the private sector. The Herald newspaper engaged me as Desk Editor with effect from February, 1999.

During the long holiday – June to September, 1999, my wife and son joined me in Yaounde to spend the holiday. It was a difficult long holiday as we struggled to live on my relatively small salary in a cosmopolitan capital city. Ekun hated our one room apartment that was not better than the one we left in Calabar. She also found it difficult to cope with the dominant local language, French.

One evening I came back from work to find her boiling with anger. When I enquired why, she told me that a neighbour came and spoke to her in French. When she told the man that she does not understand French, the man retorted: “Then what are you looking for in Yaounde? Why don´t you go back to your Bamenda”? Indeed, these were some of the challenges that contributed to the crumbling of my first marriage.

Sojourn in Europe

The Publisher of The Herald Newspaper had political ambitions and took part in the Presidential Election of 2004 in Cameroon. His heavy loss left the newspaper virtually limping. So, by the middle of 2005, he was owing salaries for more than four months.

At about the same time, the German Embassy in Yaounde, sent out a communique asking journalists who wanted to benefit from training in Germany as newspaper managers to submit their applications including at least 10 of their published write-ups.

I submitted my entries and I was selected among three other Cameroonian journalists. We were eventually to join some 50 others from other African countries, who were also selected for the refresher course.

I cooperated with the Embassy to conclude arrangements to travel to Germany on 20 August, 2005. We from Cameroon flew from the Nsimalen International Airport in Yaounde, via an Air France flight to Charles De Gaulle Airport in Paris; landing there in the early hours of 21 August. From Paris, a connecting flight took us to Frankfort, from where we travelled by train to the University town of Minze. We spent the first of our two-week training programme receiving lectures in the university of Minze. We were moved to Berlin after the first week to continue the last training week. I eventually never participated.

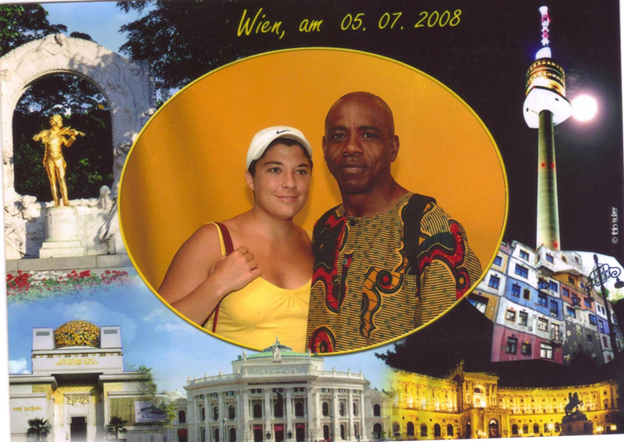

Before I left Yaounde, I had made up my mind not to return to Cameroon immediately after the two-week training. I had concluded arrangements with an Ejagham sister who also worked with the Herald but had found her way to Austria some three years earlier, had been granted asylum and was still living in Vienna.

She had advised me to do all I could so that I could cross into Austrian before my Schengen visa expired that September, or before the training programme ended because we would all be bundled into the plane immediately after the training to our home bound flights.

So, as we arrived in Berlin on the 28th of August, my attention was focused, not on attending lectures, but on how to find my way and cross into Austria. The first attempt on 29th August was abortive because I was intercepted in a train at the border between Germany and Czech Republic and sent back to Berlin. (The travails of the orphan child; a possible title of a book). By August 2005, the Czech Republic was yet to become a member of the Schengen free movement area.

It took me until August 30 to travel by night (Euronight train) from Berlin to Vienna. Mma Ayuk was waiting at the Vienna West Autoband (train station) to receive and take me home.

I spent one night in Mma Ayuk´s house in Vienna, while she made arrangements for me to be taken to the Transckeken asylum camp in the outskirts of Vienna. I got registered there as an asylum seeker from Cameroon on 31 August 2005.

After spending two weeks in the camp and answering questions why I was fleeing from my country, my asylum application was accepted to undergo processing. While it was being processed, I was posted to a more permanent asylum camp in the town of Gotzens, near Innsbruck, this time in Tirol, one of the nine regions that make up Austria. Innsbruck is the capital of Tirol.

I later learnt that as at then, Tirol was an opposition stronghold completely in opposition to the asylum policy of Vienna that was encouraging immigrants to settle in Austria. If Tirol wanted any migrants at all, they should come from Eastern Europe that was still unstable due to the disintegration of the former Soviet Union. Which means, as a black man, and unknown to me, I was in for trouble if I was sent to settle in Tirol.

More so as by the time I filed my asylum application in Vienna in August 2005, the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon had not escalated into an armed conflict. It took nearly another decade, until 2016 for that to happen. So, the opposition in Tirol claimed that Cameroon was a peaceful country so Cameroonians seeking political asylum should not be accepted.

I stayed in Gotzens for five months with my asylum case still being opposed. I was again transferred from Gotzens to another asylum camp in Schwaz in April 2006. In Schwaz, we were allowed to work with the local council for a stipend. Those of us who were single were lodged four in a room, while every family occupied a room and inmates cooked their own food.

I was to remain in Schwaz until 2013 with Vienna and Innsbruck playing Ping pong over my asylum case. While Vienna accepted my application and wanted the Tirol government to give me the privileges due approved asylum cases, the government in Innsbruck was against it.

Since many Africans in my situation helped themselves by getting married to a European woman, I also tried that method. I and Simone Keller, the lady who was teaching us the German language fell in love and decided to get married. I told her that we will work and save money to enable us to relocate and start a business in Cameroon, and she accepted.

But her parents, both of them retired accountants, never wanted anything like that. Simone was the first of their two daughters so, they could not imagine her relocating to live in Africa, worse of all Cameroon.

To convince Simone about how backward and unlivable Cameroon was, they googled images of bad roads and dwelling huts of pygmies to convince Simone about the way Cameroonians still live in the third millennium. Even worse, Simone kept it hidden from her parents that I had a son back home, whom we had agreed would join us in Germany immediately after our wedding. So, the wedding never came to be and my persecution in Europe took an uglier twist.

That was when I started seeking the help of international human rights organisations to press on the Austrian government to send me back to Cameroon. I was eventually deported in September 2013, after eight years of sojourn in Europe.

Struggle Continues

Once more in Cameroon, I spent a few days with the family in Yaounde, and then moved to Mamfe. From Mamfe, I went to the village. So much had transpired after eight years. The numerous deaths took me to neighbouring villages to condole with bereaved members of the extended family.

I spent one year shuttling between Mamfe and these villages. I eventually moved to Yaounde again in November 2014. And in January 2015, I started working with another Yaounde-based newspaper, The Guardian Post.

Unlike in Nigeria, and as a writer of English expression, you are addressing merely 20% of Cameroon´s population. Even worse, you are also trying to influence people with a very low reading culture. One Cameroonian made this absurd comment but highlighting the reality: that, if you want to hide something from a Cameroonian, put it in a book. Even if he or she sleeps on that book for 20 years, he or she will never open it to find out what is inside. It is as bad as that. Whatever we write here in the Queen´s language, is like throwing water on a deck´s back. Low appreciation of talent also translates into low remuneration, lower standard of living and other forms of frustration.

In Cameroon, only government media houses try to respect certain minimal standards of remuneration for journalists and other media men and women. This is a complete opposite with Nigeria where the private press booms; and private media houses pay better and attract the best journalists.

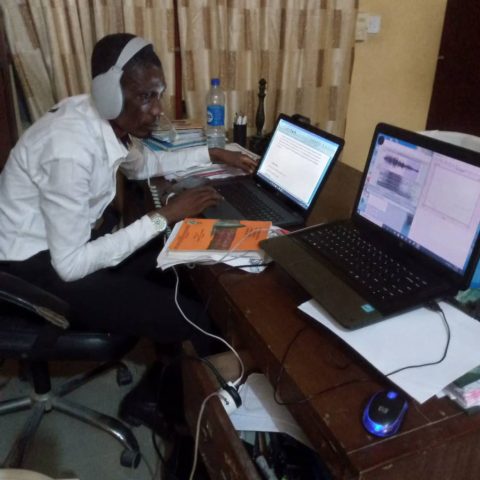

I am writing this chapter in May/June as the year 2024 is gradually winding to a close. I am still in Yaounde working with The Guardian Post newspaper. In 2015, I met Clementine Mechane Nkong and we fell in love. We got married and we already have three children. Our first child, a daughter, Enareh Ntiamba was born on 27 September, 2017. A boy, Eruhm Ntiamba, followed almost immediately, born on 27 August, 2019. Efang Obasi was born on 5 April, 2021. I am still in Yaounde writing for the Guardian Post newspaper, as the struggle continues.

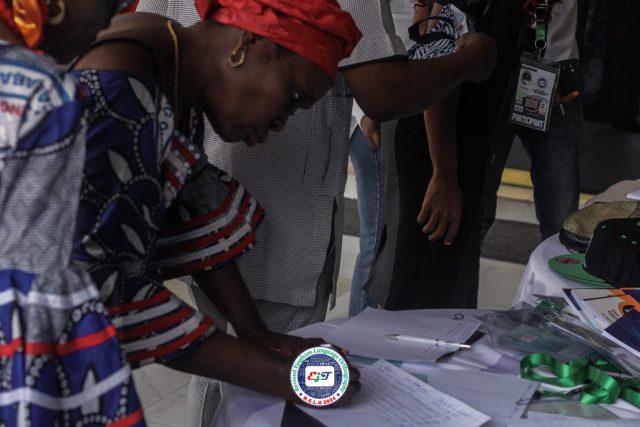

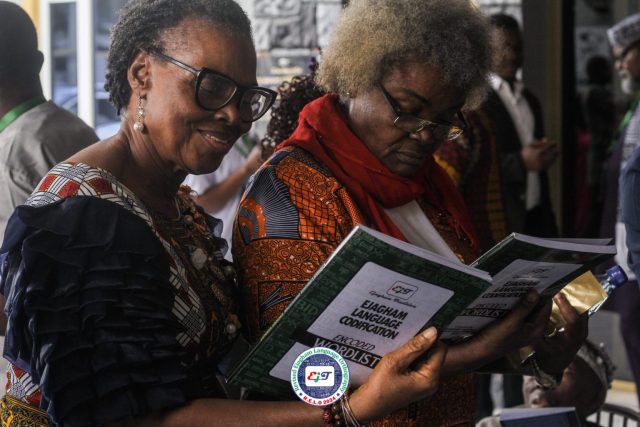

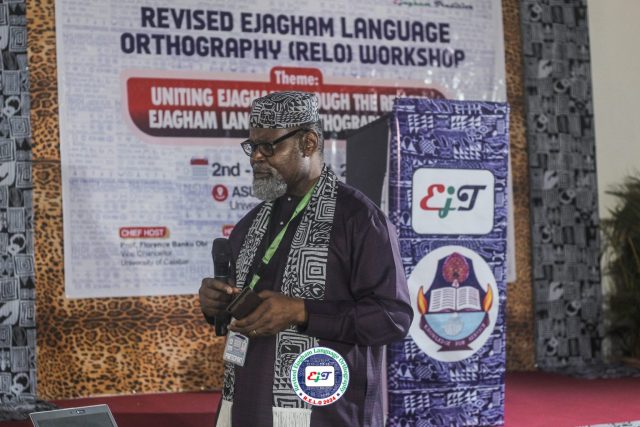

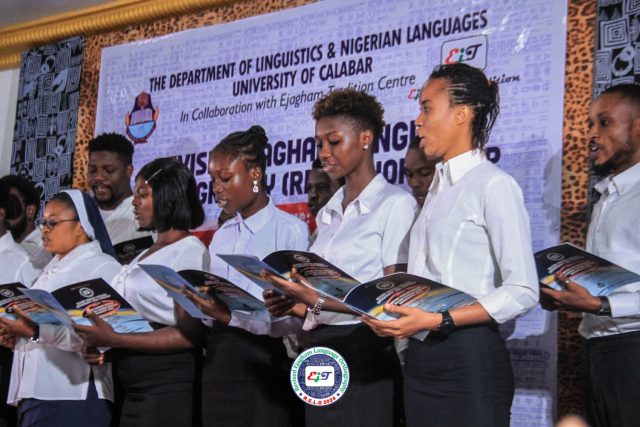

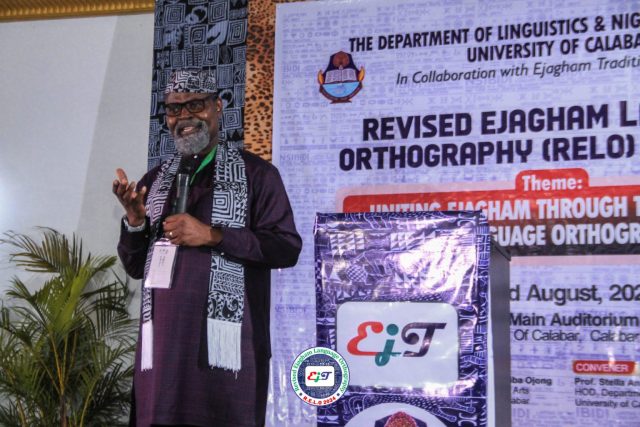

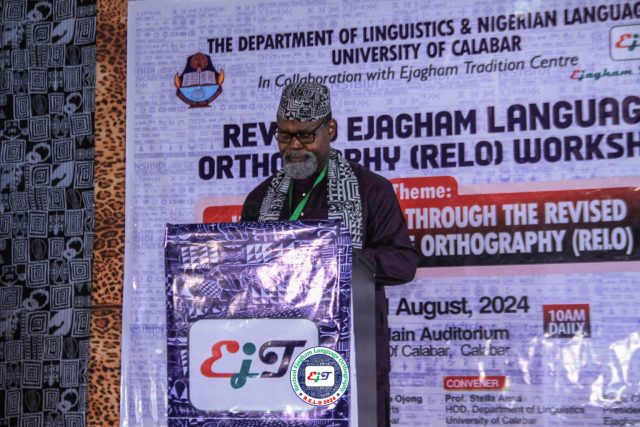

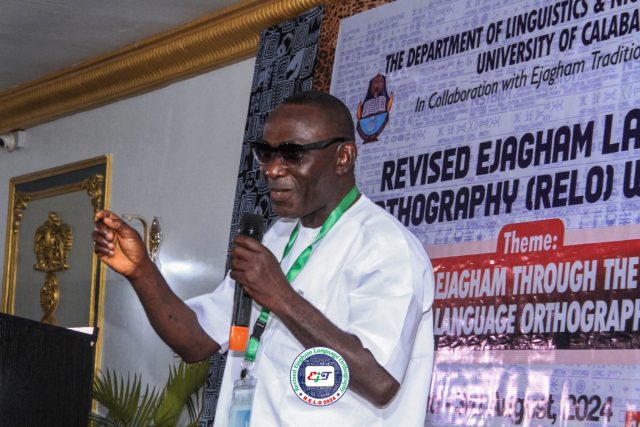

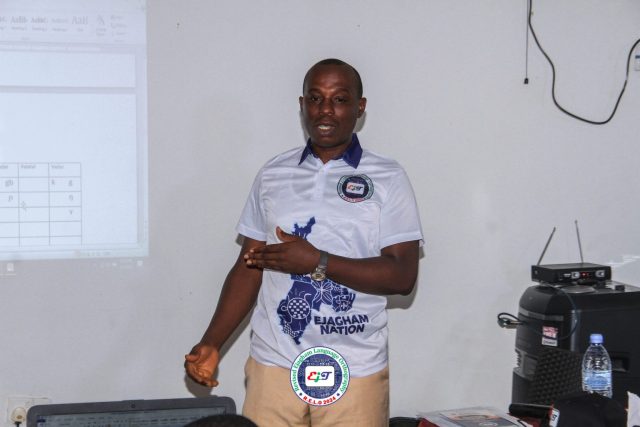

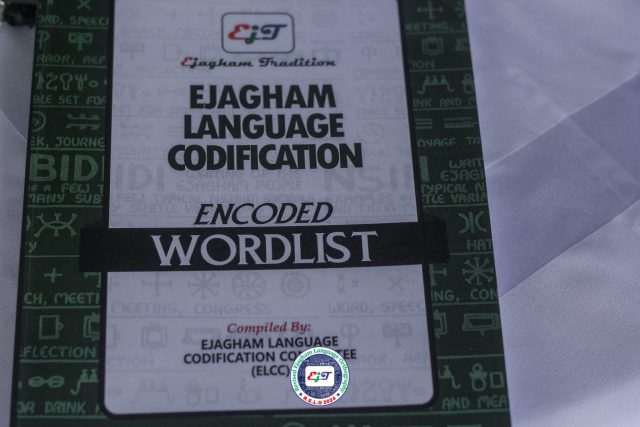

Welcome EjT

When the Ejagham Cultural revival project, Ejagham Traditions, EJT was launched, I threw my weight behind it. I have written pieces like, “Efan K’Ejagham: Ejagham for Adult Learners Part 1″; highlighting the intricacies of counting in Ejagham. I have also written, “Ichit Isor: An Introduction to Ejagham Cosmology”; “Etub Kah Ngan: An Interpretation of Ejagham Proverbs”; “Eyumojock as Focal Point of Ejagham Eco-Tourism; “The Ejagham: Our Cosmology as Cornerstone of the African World View”; “Obang in the Ejagham Nation”, among others that are awaiting publication.

My prayer is for God to keep giving the inspiration to write more books to enrich the Ejagham language; as well as providing the financial power to be able to publish what I write.

I encourage Ejagham sons and daughters worldwide, to promote the work that EJT is doing, so that we can spread our identity across the globe, because the extinction of a people begins with the extinction of their language.